By Will Myers:

One of the questions most often asked about the Moravian workbench I wrote about at WK Fine Tools a few years back concerns the tusk tenons (aka keyed tenons) that are the backbone of the design.

The tusk tenons on the bench I built over four years ago have performed flawlessly. That bench is still the one I use primarily, it travels with me to classes and on other trips, assembled and taken apart scores of times. Nevertheless, the keyed tenon seem to have a not so great reputation in the woodworking community. I think that this bad reputation comes not so much from the older forms of the joint, but from later times, more specifically arts and crafts furniture.

The early forms of the tusk tenon are generally much larger and more robust. During the arts and crafts movement in the starting in the 1870’s, tusk tenon joinery appeared quite often on bookcases, clocks, tables and chairs. Most of these were more for decoration of the piece than structural. Most are made small with a small amount of wood past the wedge. Over time, the wedges would get loose, someone would drive the wedge back in too tight and…Crack! The end grain of the tenon would blow out. That’s my theory anyway. I am not trying to knock art and crafts furniture, these small joints were fine for a bookcase or clock. Really, how much thrashing does a clock or book case get most of the time? Different story on something like a workbench though.

I have not been able to find an exact date when this type of joint came into existence. Most sources say the joint seems to have originated in central Europe. As these folks immigrated to the United States they of course brought knowledge of this type of joinery with them. The Moravians (Old Salem, NC), from which this bench design originates, came from what is modern day Czech Republic. The oldest known mortise and tenon joint is of the keyed variety excavated from a well in Leipzig, Germany. It was found to be 7000 years old.

What gives this type of joint strength and the reason it has endured millennia in my opinion, is enough wood beyond the wedge on the tenon (as the vintage ones are made) and as you will see in the video the wedge itself. As I stated earlier; when joints were made smaller for aesthetic reasons the strength was quite compromised. One point we are fortunate on, is that most of the vintage examples of these joints that have survived to the present day appearing in buildings, furniture, work benches and such are good ones to pattern new work from. For the most part the ones that were poorly designed did not survive, they went on to become compost or to stoke the cooking fire.

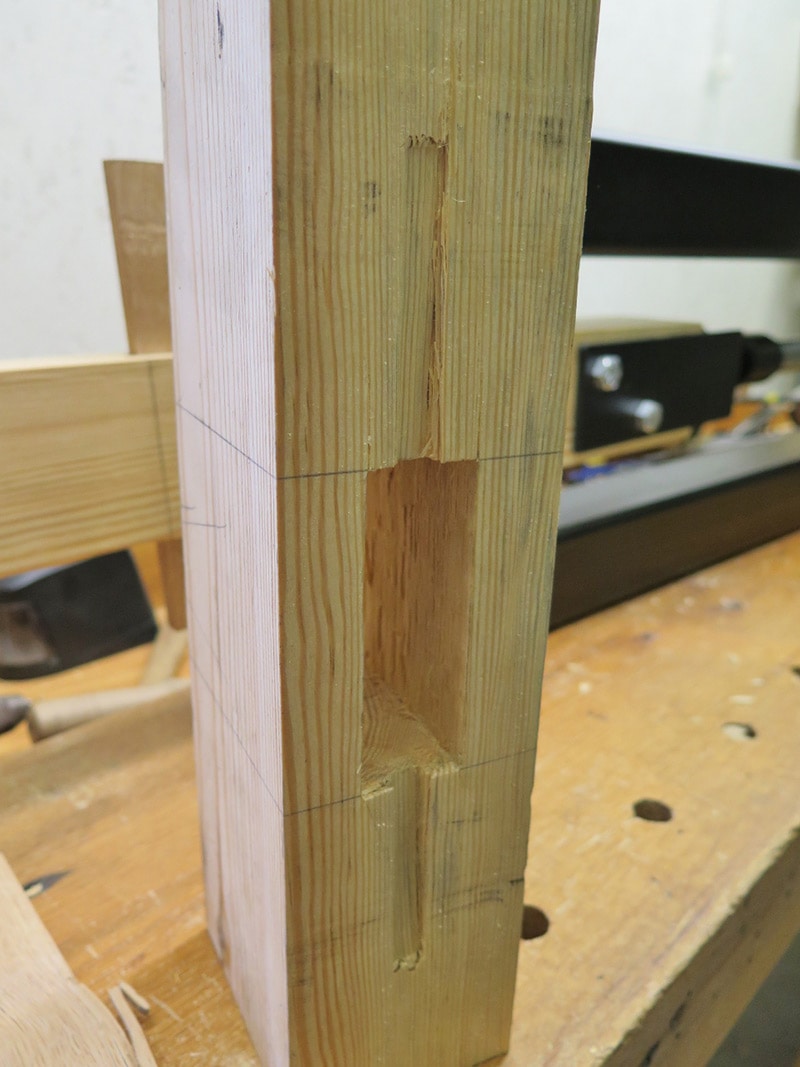

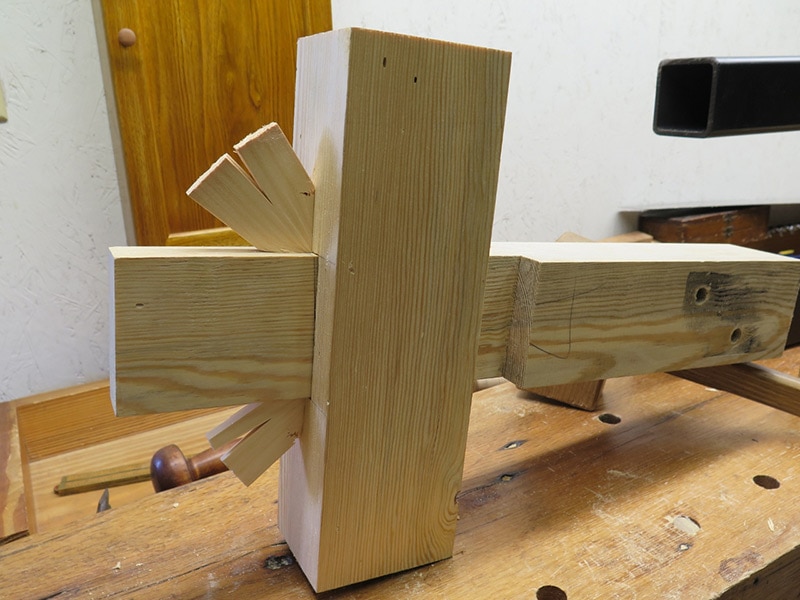

The joints I used for the test are patterned from the Moravian workbench. The mortise and the tenon shoulders on the bench joints are at a 16 degree angle. For the test joints I made them straight just so it would be simpler to mount them in the pulling apparatus. The basic dimensions of the tenon itself are 1 1/8” thick by 10” long by 3 ½” tall, made of yellow pine.

The leg is 4” wide by 3 1/8”thick, also made of yellow pine, with a mortise 1 1/8” by 3 ½” chopped thru for the tenon. The wedge is 3/8” thick by 9” long 2” wide tapered on one side to angle of about 1” in 12” made of oak. Using these dimensions you wind up with about 4” of wood beyond the wedge. Which as you will see is entirely enough.

Another good point is the orientation of the wedge. On these joints it is installed thru the wider 3 1/2” dimension of the tenon. If the wedge was installed thru the side 1 1/8” dimension of the tenon I believe, even with a wider wedge would weaken the joint….but I have not tried it yet!

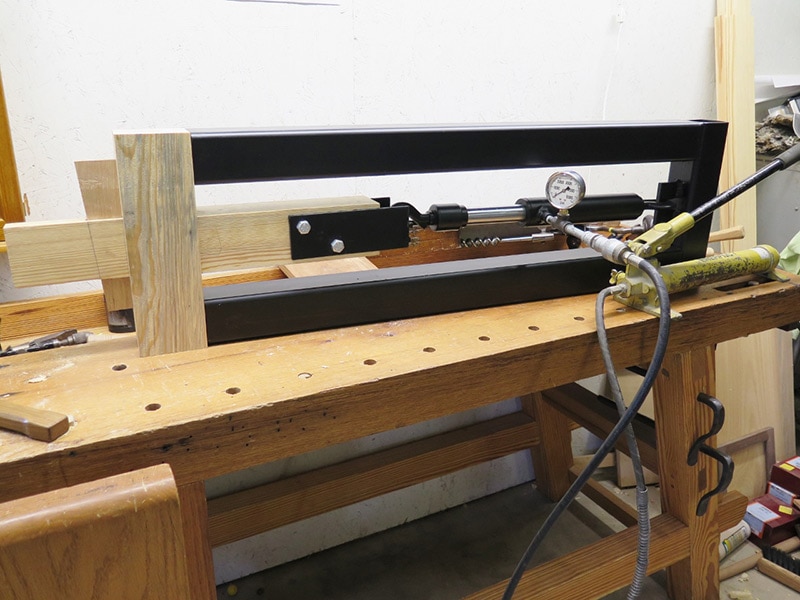

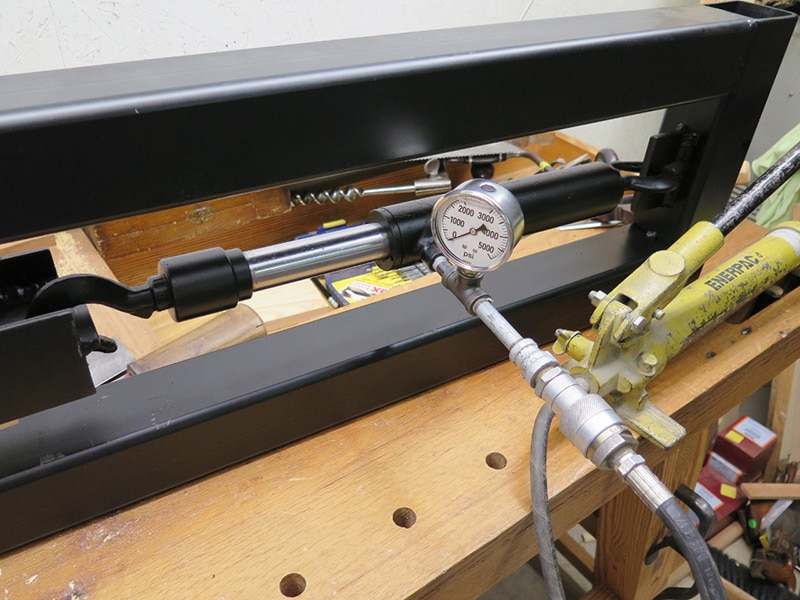

For the joint tester I made a C shaped frame from 3” square steel tubing. To pull the joints apart, a hydraulic jack and a pull cylinder make the force. I also installed a pressure gauge in the line to be able to measure the amount of force applied. By measuring the piston in the pull cylinder I was able to get a pretty close idea of the amount of force being applied to the joints, 1 psi line pressure equals 1.1 pounds of pull if my math is correct.

As of this writing I have tested around a dozen of these joints to their breaking point. What I have learned is that what I assumed and everyone else seemed to think would be the weakest part of these joints was not.

The weakest link is really the combination of the other parts of the joint. At this point I have not had a single tenon failure…..not one.

What usually causes the joint fail is the wood on the face of the leg begins to compress first (watch the video, the first cracking noise you hear!). As the pressure continues to rise the wedge eventually breaks (the pop! you hear just before the pressure gauge falls suddenly). So far they have all died in pretty much this same fashion.

I did try one with a wedge that was the same thickness but 3/8” wider than usual, the wedge broke at 4800 lbs after compressing into the leg face ¾”! The type of wood used for the wedge makes a big difference in overall strength. Fast grown white oak has fared the best around 4000 lbs, tried one of slow grown red oak, made it to about 2300 lbs.

At Roy Underhill’s prompting we did one with a white pine wedge; even that made it to 700lbs before letting go with a sudden snap! Before actually testing one of these my hope was that they would make it to at least 1000lbs before failure. I had no idea that they could go to four times that amount. What is really impressive when you think about it is there are four of these joints on a workbench. Way more than adequate I should think! Hercules would get frustrated breaking this thing!

On another note, I recently filmed an episode of The Woodwright’s Shop with Roy Underhill showing the joint annihilator in action that will air in the fall of 2016.

All the best!

Will Myers

Questions? [email protected]

Buy Will’s best-selling DVD: “Building the Portable Moravian Workbench” here.

Thicker tenons, and narrower shoulders, would permit a stronger thicker wedge which would spread the load better to lessen the face compression into the leg. It would be interesting to compare different thicknesses to find the optimum ratio of tenon thickness to shoulder thickness.

My instinct would be to make the tenon thickness equal to both shoulders added together. i.e. 2:1 tenon to shoulder.

I built the bench with the tusk joint. I can’t say that I tested it to failure, but it was a very fun and satisfying joint to make….oh, yeah, and the bench is plenty rigid. On a side note, I’m glad to see your battle scarred Enerpac pump…..I worked there for a number of years designing their powered pumps!

I a curious if the failure mode is any different in the actual design on the workbench since it is an angled tusk tenon design. I was able to see Will’s Moravian workbench at WIA 2014 in Winston-Salem – the bench was (and is) as sturdy as you could want with the additional advantage of being able to knock it down, move it and put it back together quickly.

Hi Will, That is an awesome post! As an fyi, and you may already know this, the multiplier for cylinders is different for extend and return. In other words for extension, you use the area of the bore multiplied by the pressure to get the force. In retraction, like your test, you would subtract the rod cross section from the bore area to get the acting area. Whatever the numbers are, the forces that the joint can take are truly… Read more »

A great tutorial, thanks guys!

Hi! Here in Sweden the tusk joint has never gone out of fashion, but is the normal joint whenever you need a strong and stable frame for a table, a bench, a bed or whatever sturdy piece of furniture intended. Especially good for things that you only use seasonally – garden furniture, party tables etc. Of course the boat cradle for my 2,5 ton sailing boat uses tusk tenons – then it can be disassembled during the summer. (Swedes fancy… Read more »

Thanks for your comment Jonas from Sweden! Yup, there’s only one Roy!

What a great post explaining the joint in detail and then testing it! I wonder if it would be useful to put a hardwood shim between the leg and the wedge. It would be interesting to see what it would take to get the tenon to fail. I hope this post qualifies for the clamp giveaway! Alternative choices for me are the shaker candlestick stand video, the wood and shop blue logo t-shirt (m), or the bedrock handplane mug (any).… Read more »

I think an important parameter would be the applied load at which the wood on the leg (that butts up to the oak wedge) starts to permanently deform. That’s the amount of load that is going to cause the bench to start ‘wobbling’, isn’t it? If you were to then tap the wedge tighter, it wouldn’t mate up exactly to the leg (due to the permanent deformation), which seems to me to mean the stability of the bench would be… Read more »

Hi Fred, we’re still reading comments.